Cameras on boats or electronic monitoring as it is sometimes known, is a cost-effective solution to provide independent monitoring of the catch and bycatch in commercial fisheries. Cameras have already been installed in a number of different fisheries in both Australia and overseas, providing data that gives us an accurate picture of what is being caught.

Why do we need cameras on boats?

Australia’s oceans are home to incredible wildlife, from dugongs, turtles and sawfish in our tropical north to dolphins and Australian sea lions around our southern coast. However, many of these species are threatened by commercial fishing, with populations in decline.

Unfortunately, threatened species are often caught as bycatch in some of Australia’s commercial fisheries. This incidental catch can injure and kill our precious threatened species, and is often viewed as one of the most significant fisheries sustainability issues in the country.

Sadly, at the moment we do not know the scale of the problem. Fishers are meant to report their interactions with these iconic species, but we know that in many of Australia’s highest-risk fisheries, these interactions are being under-reported¹²³⁴. This can’t happen if we want a future for our threatened ocean wildlife. We need an accurate picture of what is being caught, so that we can manage the risks of fishing and ensure our threatened species can recover.

How does it work?

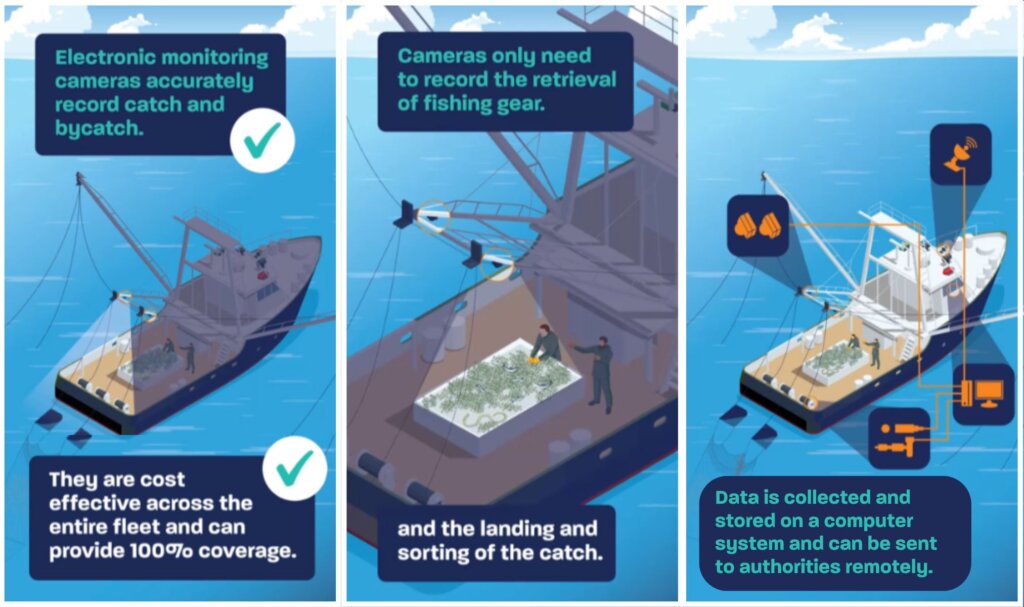

Electronic monitoring systems consist of a series of cameras, computer systems, data storage and in some cases gear sensors that are used to independently monitor fishing activities. Cameras are only required to capture the landing and sorting of catch and the discard of bycatch. The data is then sent to reviewers (either independent or departmental employees) via the cloud or external hard drives for review of fishing activities.

In the future the use of artificial intelligence may automate the process of footage review, significantly reducing costs and increasing the speed in which review is undertaken. A number of artificial intelligence trials are already underway, including in Australian fisheries, but are currently limited by a lack of images required to train the artificial intelligence software.

Cameras on boats are not new, these systems have been trialled and implemented in fisheries worldwide for more than 20 years⁵. In Australia, electronic monitoring has been a mandatory requirement in the Commonwealth managed Eastern Tuna and Billfish Fishery (ETBF), Western Tuna and Billfish Fishery, the Southern and Eastern Scalefish and Shark Fishery (SESSF) Gillnet, Hook and Trap sector and the Midwater trawl sector of the Small Pelagic Fishery since 2015.

The New Zealand Government has recently invested NZ$68m to rollout electronic monitoring systems on up to 300 inshore fishing vessels comprising 85% of total catch. The program prioritises high risk fisheries such as gillnet and trawl fisheries, with the program to include longline and purse seine vessels in the coming years⁶.

One of the main advantages of cameras on boats as an independent monitoring is that it is cost effective at scale. Best practice identifies that 100% of vessels operating within a fishery should have independent monitoring coverage⁴⁷⁸⁹.

Are there other options?

Historically, independent scientific observers have been present on a proportion of fishing trips to gather independent information on fishing operations. Using observers can have some benefits. In particular scientific samples can be taken to support research projects, species that are difficult to identify can be physically handled and identified, and individuals can’t be lost out of the camera’s line of sight. However, they are considered prohibitively expensive to deliver robust levels of coverage.

The high cost of scientific observers in commercial fisheries has typically led to low levels of coverage (often less than 5% of fishing effort), particularly in large fisheries with high fishing effort. Low levels of independent observation does not provide the confidence and certainty in reported levels of bycatch.

If independent scientific observers are only present on a proportion of fishing effort then an issue known as the observer effect can occur. The placement of scientific observers on vessels for some trips has been shown to influence where fishing may take place, for example fishing in an area where bycatch of threatened species is known to be lower, or lead to changed operational behaviours such as correctly reporting bycatch or changes to handling procedures⁶⁸. This can lead to significant bias in the dataset collected by independent scientific observers, limiting the usefulness of the data.

Do we need cameras in all Australian fisheries?

No, there are many fisheries where cameras on boats are not required because the fishery is considered low-risk. Fisheries like the Corner Inlet Fishery in Victoria, or hand harvest fisheries like tropical rock lobster in Queensland, or abalone in our southern States have next to no threatened species bycatch and are considered a low risk.

Other very small fisheries with just a handful of operators may be suitable for independent observers as an alternative to cameras, should that be cost-effective to achieve 100% coverage.

Cameras on boats are a good fit for high-risk fisheries where we need high levels of independent monitoring. 100% coverage in these high-risk fisheries gives fisheries managers the accurate data required to manage fishing and its impact on threatened species, and the community confidence that fishing is not having a detrimental impact on the broader environment.

Trawl and gillnet fisheries tend to be responsible for the majority of threatened species bycatch in Australia, with many of these fisheries considered a high-risk and good candidates for cameras on boats.

Community and Commonwealth expectations

Regulatory bodies, international agencies and seafood consumers are paying ever-increasing attention to seafood sustainability and the impact of wild-caught seafood on threatened species populations. This includes the collection of accurate data on catch and bycatch, and high levels of independent monitoring are a key feature of best practice fisheries management.

Independent monitoring and cameras on boats are a crucial part of our GoodFish assessments, without it we just cannot have the confidence that high-risk fisheries are not impacting our iconic wildlife. With more and more consumers seeking out sustainable seafood options it is clear that the community expects our seafood not to come at the cost of threatened species.

In Australia, Wildlife Trade Operation (WTO) accreditations are required by the Commonwealth under the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (EPBC Act) in order for a species to be exported internationally and to allow interactions with listed threatened species with indemnity from prosecution. In accrediting a fishery as a WTO, the Commonwealth Department of Climate Change, Energy, Environment and Water undertakes an assessment of the fishery against the Guidelines for the Ecologically Sustainable Management of Fisheries.

Accredited fisheries often have conditions placed on them to ensure that they meet these guidelines and if a condition is not met the Federal Environment Minister must revoke the WTO. At the moment some high-risk fisheries in Australia already have conditions requiring cameras on boats. While some of these fisheries are on track to meet these requirements, others are falling behind on their implementation.

With Queensland home to the Great Barrier Reef, a World Heritage Site under significant pressure, expectations are higher. In March 2022, UNESCO and IUCN, scientific advisors to the World Heritage Centre undertook a reactive monitoring mission to assess the health and management of the Great Barrier Reef World Heritage Area. In November 2022 they published their Reactive Monitoring Mission (RMM) report, which included a recommendation to implement cameras on boats on all gillnet and trawl vessels on the GBR.

What needs to happen next?

We need to see the different jurisdictions that manage fishing in Australia speed up their implementation of putting cameras on boats. Too few of Australia’s high-risk fisheries currently have sufficient levels of independent monitoring, which means the community can not have confidence in the bycatch data.

While some States are further along in the journey than others, States like NSW, QLD and WA still need to develop detailed policies that outline which fisheries will require cameras on boats, what vessels it applies to, how footage will be reviewed and how summary data will be made publicly available. In all jurisdictions the rollout of cameras on boats needs to be prioritised and rapidly implemented to help ensure that our fisheries are not having a detrimental impact on threatened species and community and other stakeholder expectations are met.

What can you do?

The Federal Environment Minister, the Hon Tanya Plibersek has the ability to apply conditions to a fishery under our Federal Environment laws. We are urging Minister Plibersek to ensure that robust time-bound conditions are applied to all high-risk fisheries requiring cameras on boats and independent monitoring, and that these conditions are delivered on by the different jurisdictions.

By emailing Minister Plibersek, you can help ensure that we get an accurate picture of what is being caught in Australia’s highest risk fisheries, and help protect Australia’s incredible wildlife.

References:

- Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority 2019, Great Barrier Reef Outlook Report 2019, GBRMPA, Townsville.

- Assessment of the Queensland East Coast Otter Trawl Fishery, December 2021, Commonwealth of Australia 2021’

- Wueringer, B. E., Biskis, V., & Pinkus, G. (2023). Impacts of trophy collection and commercial fisheries on sawfishes in Queensland, Australia. Endangered Species Research, 50, 133-150. https://doi.org/10.3354/esr01222

- Kirkwood, R. and Goldsworthy, S.D (2024). Assessment of dolphin interactions, effectiveness of Code of Practice and fishing behaviour in the South Australian Sardine Fishery: 2022. Report to PIRSA Fisheries and Aquaculture South Australian Research and Development Institute (Aquatic and Livestock Sciences), Adelaide. SARDI Publication No.F2010/000726-14. SARDI Research Report Series No.1209.58pp

- Van Helmond, A.T.M., Mortensen L.O., Plet-Hansen K.S., Ulrich C., Needle C.L., Oesterwind D., Kindt-Larsen L., Catchpole T., Mangi S., Zimmermann C., Olesen H.J., Bailey N., Bergsson H., Dalskov J., Elson J., Hosken M., Peterson L., McElderry H., Ruiz J., Pierre J.P., Dykstra C., and Poos J.J. (2020). Electronic monitoring in fisheries: Lessons from global experiences and future opportunities. Fish and Fisheries 21: 162–189.

- Ministry for Primary Industries. “On-Board Cameras for Commercial Fishing Vessels | MPI – Ministry for Primary Industries. A New Zealand Government Department.” Www.mpi.govt.nz, www.mpi.govt.nz/fishing-aquaculture/commercial-fishing/fisheries-change-programme/on-board-cameras-for-commercial-fishing-vessels/.

- Course, G.P., Pierre, J., and Howell, B.K., 2020. What’s in the Net? Using camera technology to monitor, and support mitigation of, wildlife bycatch in fisheries. Published by WWF.

- Babcock, Elizabeth & Pikitch, Ellen & Hudson, Charlotte. (2011). How much observer coverage is enough to adequately estimate bycatch.

- Morrell, T. (2019). Analysis of ‘Observer Effect’ in Logbook Reporting Accuracy for U.S. Pelagic Longline Fishing Vessels in the Atlantic and Gulf of Mexico. HCNSO Student Theses and Dissertations. https://nsuworks.nova.edu/occ_stuetd/511