Spanish mackerel are often thought of as iconic in Queensland. They are a staple in fish and chip shops, particularly in north Queensland, with a number of fishing businesses reliant on the species as their main source of income in supplying that market. The species is also sought after recreationally throughout the Great Barrier Reef, in southern Queensland and northern New South Wales.

What is the situation?

You may have heard the alarming news that the east coast Spanish mackerel population is in a really bad way. You may also have heard some fishers questioning the science behind the stock assessment, and stating that the population is healthy. Below we explain what is going on with Spanish mackerel, why it is important to have a healthy fishery, and what you can do to improve the outlook for these species on the GBR.

What does the science tell us?

In the grand scheme of things, Spanish mackerel are a data rich species, with nearly 80 years of commercial catch information and thousands of fish that have been measured and had their age estimated. Having a strong understanding of their biology, and a large set of data – gives us confidence in the outputs of a stock assessment.

Scientists from the Queensland Department of Agriculture and Fisheries completed an updated stock assessment in 2021 that found that the east coast Spanish Mackerel stock is between 14 and 27% of the unfished biomass, with the most likely scenario that it is currently at 17% of unfished levels. This stock assessment used a sophisticated scientific model, which was then independently peer-reviewed and endorsed by the Queensland Fisheries Sustainable Fisheries Expert Panel.

Generally speaking, a stock below 20% of its unfished population is considered depleted and overfished. A cause for alarm. Queensland Government policies, and national guidelines within Australia state that a fishery should be closed if a population falls below 20%, to allow the population to recover to healthy levels.

Continued fishing of a species below 20% of its unfished population can push a species to the point of collapse, as has been seen with species like cod in the north Atlantic.

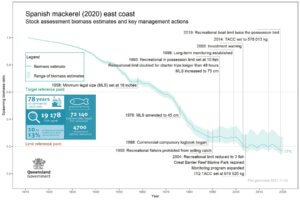

The population trends and major management changes that have occurred in the Spanish mackerel fishery. Source Queensland Department of Agriculture and Fisheries. Source.

While this stock assessment estimates the population of Spanish mackerel to be considerably lower than the previous estimate (30-50% of unfished levels in 2016), it does not come as a big surprise to many.

Spanish mackerel aggregate in what is one of the most notable and predictable spawning events on the GBR. It is this period between September and November when the bulk of the catch is taken, as it is relatively easy to catch lots of fish. However, the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority (1, 2) have long held concerns regarding the targeting of spawning aggregations and research has shown a decline in the number, frequency and size of spawning aggregations at specific reefs in north Queensland (3).

Why are fishers questioning the science?

A number of fishers, both commercial and recreational, are questioning the science being used to inform the management of Spanish mackerel. This is playing out in both the media and on social media.

Unfortunately, this appears to be part of a trend where a minority question science when it tells us something we don’t want to hear. A trend that is increasingly frequent when it comes to the Great Barrier Reef.

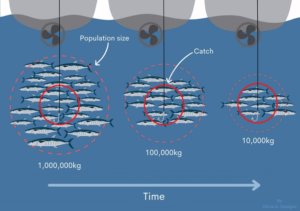

Fishers are also reporting that Spanish mackerel are as easy to catch as ever, and the same number of fish are still being landed. While this may be true, it is caused by a situation known as hyperstability. Hyperstability means that while a fish population is in decline over a period of time, the catch and catch rates remain stable (generally the pattern you would expect to see is of declining catch and catch rates as a population declines). This can be put down to the spawning aggregations of Spanish mackerel, with the fish being particularly vulnerable and easy to catch during that period. So fishers continue to catch the same amount of fish, but don’t realise the population of the species they are targeting is getting smaller each year.

Hyperstability is when catches and catch rates remain stable over time, but the population of a fish is in decline.Image source: JCU Fish and Fisheries lab. Source.

Why are Spanish mackerel so important?

The Great Barrier Reef is a global icon, a World Heritage Area, and dear to the hearts of many Australians. But it is under unprecedented pressure from global warming. Additionally, water pollution and unsustainable fishing practices also take a toll on the Great Barrier Reef and its incredible ecosystems.

To give our Reef a fighting chance, we need to do all that we can to tackle the local pressures of unsustainable fishing practices and water pollution, to increase the resilience of the Great Barrier Reef. To increase that resilience, we need healthy fish populations and diverse and functioning ecosystems. Fisheries management within a world heritage area should be held to the highest possible standards, and that includes ensuring that fish stocks are not overfished.

Spanish mackerel are a higher order predator and play an important role in the food chain. They are also of high economic and social value to the fishing businesses and recreational fishers that catch them.

It is clear that there is a lot to lose. Doing nothing is not an option, continued fishing could push Spanish mackerel close to the point of collapse, at which point there are no economic or social benefits, and there will be flow on broader effects within the ecosystem.

What needs to happen next?

The Queensland Government is midway through implementing their Sustainable Fisheries Strategy 2017-2027. The Strategy has admirable targets, including growing and maintaining fish stocks to healthy levels of 60% of unfished levels, and ensuring no fish stocks are overfished by 2027.

But we are at a turning point, we need strong management action to ensure that we can meet those targets and recover east coast Spanish mackerel as quickly as possible.

Queensland Government policies and global best practice state that when a fish stock is below 20% biomass, the fishery should be closed. Based on the best available science, our view is that the fishery should be closed for two years to allow the stock to recover to above 20%.

Once that has occurred, we could support a gradual introduction of fishing pressure, with strict commercial and recreational catch limits, that restrict harvest in line with stock assessments to recover the fishery to a sustainable level (40% of unfished levels) within 10 years. This would include:

- Considerably lower Total Allowable Commercial Catches for the commercial sector

- A 1 fish possession limit and 2 person boat limit for the recreational sector

- A 12 week fishing closure for all sectors during the key spawning season for both the northern (September-November) and the southern parts of the fishery (early in the calendar year)

- Better recreational catch data including recording of retained fish

- Cooperation with New South Wales to ensure corresponding management arrangements in both States

Of course there will be commercial and recreational fishers that are impacted by any closures or reductions to the allowable catch implemented by Fisheries Queensland. This will have very real impacts on livelihoods and people, and we are sympathetic to that. But when a species is in a perilous position, such as Spanish mackerel is, difficult decisions need to be made to ensure sustainability and deliver those long term benefits to the community.

What can you do?

The Queensland Government is currently consulting with the public on what management action should be taken for Spanish mackerel. Please complete the quick survey here, so that Fisheries Queensland receives balanced feedback, and a responsible decision is made on the future management of the species.

References:

- Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority 2014, Great Barrier Reef Outlook Report 2014, GBRMPA, Townsville

- Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority 2019, Great Barrier Reef Outlook Report 2019, GBRMPA, Townsville

- Tobin, A., Heupel, M., Simpfendorfer, C., Buckley, S., Thurstan, R., and Pandolfi, J.M. (2014) ‘Utilising innovative technology to better understand Spanish mackerel spawning aggregations and the protection offered by Marine Protected Areas.’ (Centre for Sustainable Tropical Fisheries and Aquaculture, James Cook University: Townsville) 70pp